In 1984, an extraordinary event occurred. A lost tribe, of about a dozen Pintupi Aboriginals was discovered, living in the remote wilderness of the Gibson Desert on the border between Western Australia and the Northern Territory. They were still carrying on their traditional nomadic way of life, a way of life sanctioned by millennia.

While all the other Pintupi Aboriginals in the area had been rounded up in 1962 and settled on Government stations further east, far from their ancient lands, this small tribe, (in reality no more than a family group) had contrived to escape the net.

They continued to live by hunting and gathering. Their deep knowledge of the land, its flora, its fauna, its hidden water holes, allowed them to survive in an apparently inhospitable environment. They continued to travel the ancient Songlines, that codified this knowledge and defined their harsh but beautiful world. And they continued to perform the time-honoured rituals and ceremonies of their culture.

Occasionally they might sight parties of prospectors, or see aeroplanes pass overhead, but they always remained hidden. They had no contact with the modern world of white, twentieth-century Australia. Until 1984. It was then that they were found by a party from a recently re-settled aboriginal outstation at Kiwirrkuru.

The discovery created international headlines. It also created a new life for the wandering tribe. The contact was timely. The young men of the group needed to find wives from outside their immediate family. They moved en masse to Kiwirrkuru, a tiny settlement of some hundred-and-eighty people on the edge of the Gibson Desert which has the distinction of being the most isolated town in Australia.

Despite this isolation, the tribesmen soon began to learn something of the wider world, and not least the wider world of contemporary Aboriginal culture and the Aboriginal art movement. In 1987, one of the tribesmen, Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri approached Daphne Williams of Papunya Tula Artists, the pioneering Aboriginal artists’ co-operative in Alice Springs, with a request for painting materials. He received encouragement and advice from other Papunya Tula artists.

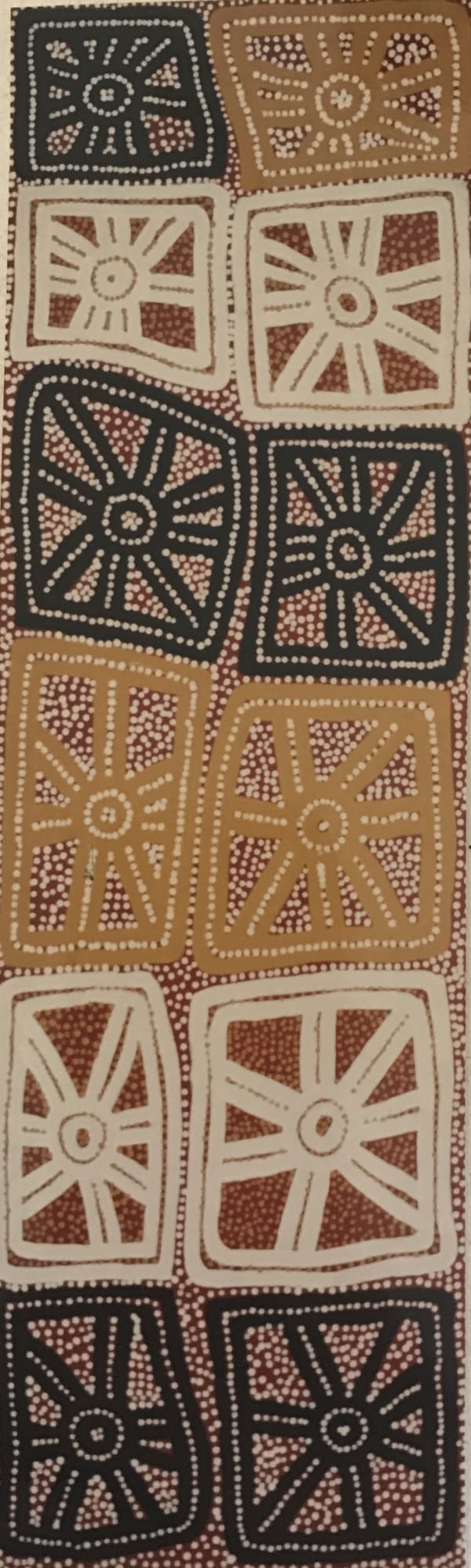

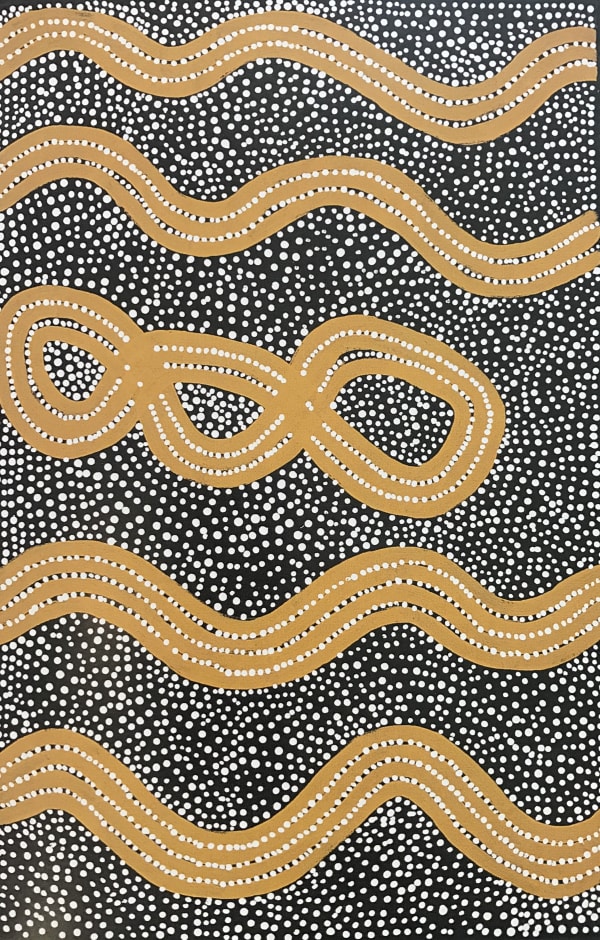

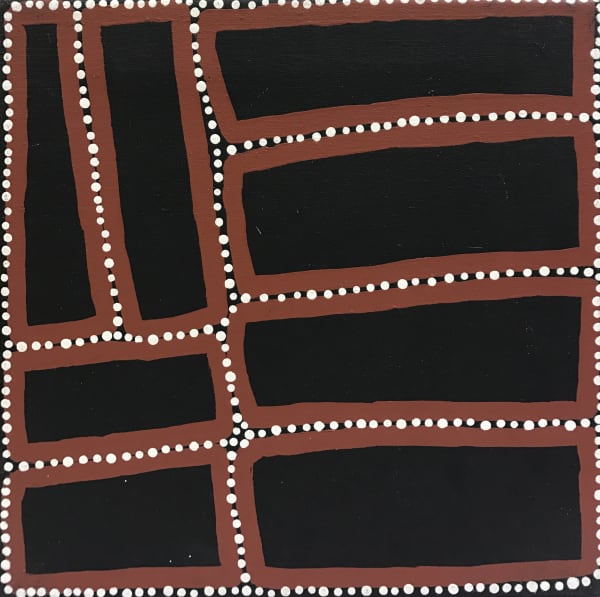

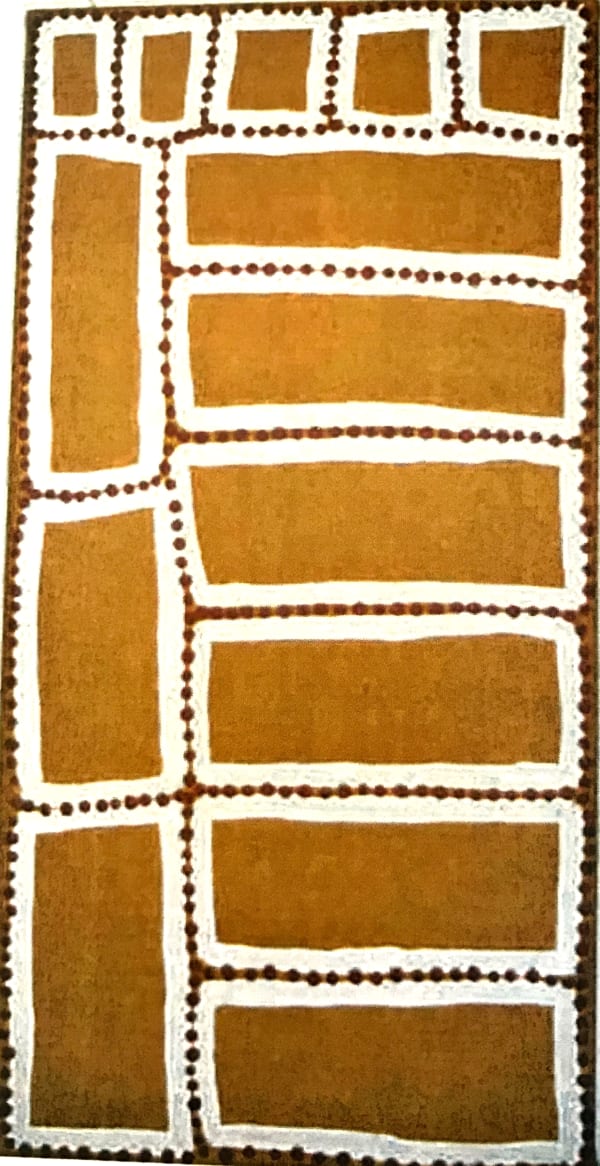

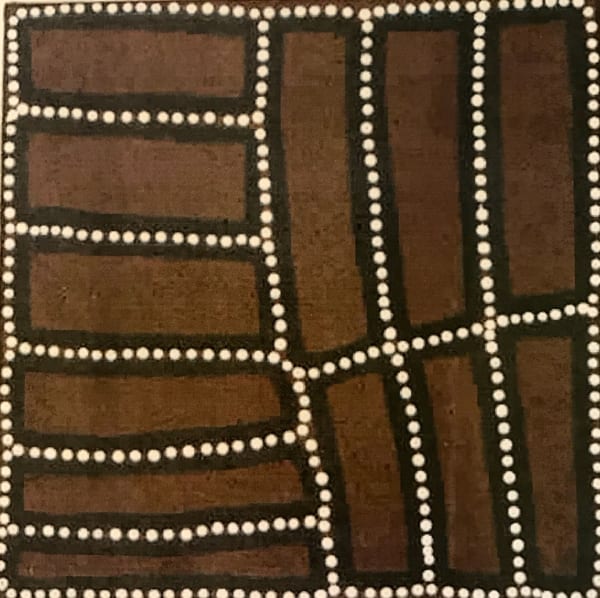

Back at Kiwirrkuru he instructed his brother Walala Tjapaltjarri in his new discipline. They both began to paint on canvas. Previously their artwork had been for ceremonial purposes only; their media had been body painting and sand designs. Acrylic paint on canvas offered them a new challenge and a new opportunity. They began to set down the stories of their land, using the images and motifs of an unbroken cultural tradition stretching back tens of thousands of years. The work, from the start, exhibited a rare and powerful assurance.

It is tempting to equate this power to the strength and vitality of the brothers’ cultural background. And there is probably some truth in this equation. But it is not the whole story. Warlimpirrnga and Walala are exceptional artists, exceptional image makers. They create great paintings. The power of their work transcends mere ethnicity, and the specifics of its subject matter. It speaks with great clarity and directness.

The quality of their work was recognised at once. Both Warlimpirrnga and Walala have had important solo exhibitions in Melbourne and Sydney, and each is represented in national collections in Australia and Europe. This is the first London exhibition of their work, and I am very proud to present it.

Rebecca Hossack

Tingari Cycle

The Tingari are the key figures of Western Desert Aboriginal cosmology. They are the ancestral beings who created the Universe - and everything in it - during the Dreamtime. Entering a dark silent void, they created the Earth, the Sun, the Moon and the stars. As they roamed over the surface of the Earth life sprang up in their wake - rivers, valleys, lakes, plants, animals and people.

The Tingari took many forms, but they were endowed with human traits; they loved, were jealous, kind and cruel. Having completed their journeys they sank back into the ground or some remained on earth - transformed - as features of the landscape: rocky outcrops, waterholes, caves and valleys. Knowledge of these sites, and the stories of their origins, have been preserved over millennia by the Aboriginal peoples.

The ritual ceremonies and song cycles recording the Dreamtime journeys of the ancestral beings and explaining the creation of the land are known as Tingari cycles. They define the landscape and man’s place in it.

There was always a strong visual element in the Tingari ceremonies. A pictorial scheme of the Tingari cycle would be set down on the ground in different coloured earths as a huge, but ephemeral, sand drawing a kind of map-cum-storybook, teaching the living history of the land, its hidden resources and pathways. Only in recent years have these Tingari cycles been recorded in more permanent form - in acrylic paint on canvas.

Nevertheless the sacred element remains strong. Each feature of the landscape - the story that explains it and the right to depict it in whatever media - is assigned to the custody of a family - or skin group - within a tribe, and then further division is made between individual members of that family. Each member is made custodian of some specific part of the Dreaming story. Many elements of the Tingari ceremonies remain secret - open only to initiates. Sacred details are set down but their meanings are not revealed.

-

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle, 1999

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle, 1999 -

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1997

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1997 -

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle, 1999

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle, 1999 -

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1997

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1997 -

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1997

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1997 -

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999 -

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1997

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1997 -

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999

Walala Tjapaltjarri, Tingari Cycle , 1999