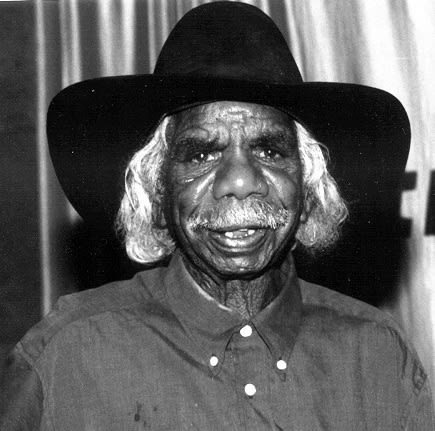

Long Tom Tjapanangka c.1930-2006

Long Tom Tjapanangka and his first wife Marlee Napurrula began painting for the Ikuntji Women’s Centre in late 1993, following its opening in 1992. Ikuntji (Haasts Bluff) is about 230 kilometres west of Mparntwe (Alice Springs) in the land of the Luritja people. The ancient ranges that dominate the landscape around the community offer a spectacle of rich natural beauty and immense ceremonial significance. In recent years, Tjapanangka also collaborated with his second wife, Mitjili Napurrula.

At the time of the proclamation of Haasts Bluff Aboriginal Reserve in 1940, Ikuntji was a ration depot. For Warlpiri, Pitjantjatjara, Pintupi and Arrernte people, it offered refuge from the harsh droughts of the early twentieth century, pastoral incursions into Aboriginal lands and the terror of the Coniston massacre. Today, the Ikuntji Arts Centre organises bush trips for the artists and their amilies back to their homelands. These journeys are a source of inspiration for painting and an opportunity to affirm traditional links with the land.

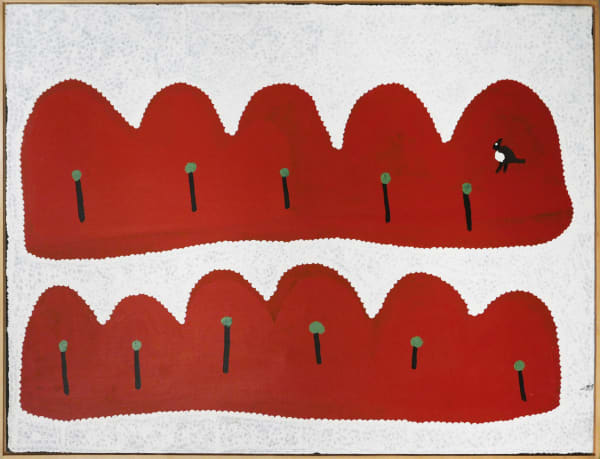

Tjapanangka’s paintings celebrate the striking topography of the country he travelled through as a young man while working as a stockman and police tracker. The artist’s stated intent was to paint for ‘everyone’, rather than making works of implicit sacred significance. Tjapanangka’s method was akin to that of his contemporaries Emily Kam Ngwarray, Kutuwulumi Purawarrampatu and Rover Thomas. Like the two distinguished women artists, Tjapanangka was diffident in the face of scrutiny from outsiders as to the ‘meaning’ of his work. And, like the late Rover Thomas, he lived and worked as an artist far away from his birthplace on the Northern Territory and Western Australia border.

The inherent elusiveness of Tjapanangka’s works is a direct contrast to their formal pictorial vigour. Although the abstract forms of tali (sandhills) and puli (rocks)that recur in Tjapanangka’s paintings are features of the desert landscape, his artistic tendency towards the figurative is anomalous to classic Western Desert painting. His technique also diverges from that of the neighbour-ing Papunya Tula artists – his dense, clotted application of paint evokes a palpable sense of country. Tjapanangka’s paintings present an idiosyncratic fusion of artistic influence that reflects the dynamism and cultural hybridity of the Ikuntji community.