Jimmy Pike

Born at Kurntikujarra in the Great Sandy Desert of Western Australia during the Second World War, Walmajarri artist Jimmy Pike was just 13 when his people became some of the last to walk into the European-owned cattle stations that were gradually taking over their desert environment. He became a stockman at Cherrabun station near Fitzroy Crossing, and learnt to ride horses and round up cattle. (Pike's English-language name was borrowed from that of a famous Australian jockey).

Nearly twenty years later, he found work as a carpenter building community housing for the Aboriginal settlement at Fitzroy Crossing. A tribal murder in 1980 resulted in his imprisonment in Fremantle, and it was here that he came into contact with the techniques and materials that would come to define his contemporary art practice. Whilst in prison, his mentors, Stephen Culley and David Wroth, immediately recognised the extraordinary power of his early artistic explorations. His imagery was charged with a sacred connection to his ancestral Country, and rendered in bright texta colour drawings and vigorous linocut printmaking. It was in prison too that Pike met Pat Lowe, a British-born woman working as a community welfare officer who had dreamed of a life in Australia since childhood. On his release in 1986 Pike and Lowe married, and together they returned to his desert homeland where they lived for the next three and a half years.

Pike maintained a close and creative friendship with Culley and Wroth, who had established a conceptual design company, Desert Designs. Together, they transposed Pike’s traditional imagery and patterns onto fabric, clothing and domestic items. While decorating the body and useful objects fitted well with Aboriginal traditions, Desert Designs managed to maintain the cultural integrity of Pike’s interpretations of ancient iconography while offering a range of new interpretive possibilities.

With Jimmy as their artistic leader, the company worked with a number of other artists and created a new industry that developed throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s, ethically manufacturing and licensing Aboriginal designs for some of the world’s most prestigious companies including Sheraton, Hermes, and Oraton amongst others. This created the income that enabled Jimmy Pike to live a free and independent life as an artist in his own country.

The unique geographical and spiritual setting of his desert homeland is the wellspring of Pike’s dynamic creativity, which became identified with its compelling, sinuous line and intense colour. Many of his paintings and prints represented maps and narratives about this country and incorporated decorative patterns his people used on spears, boomerangs or utensils. Yet Pike also brought an individual perspective to his subject matter, which gave his work a very contemporary flavour. His two-dimensional flattened figures and energetic designs conveyed a hard-edge modern sensibility. While he imparted his knowledge and expressed his deep feelings for his ancient traditions, he carried this a step further by responding to more immediate experiences and ideas that fed into his rich and active imagination. Rediscovering and maintaining the sacred sites and waterholes that once sustained his family’s nomadic journeying became Jimmy’s passion and helped him to consolidate the mythological world of ancestors and Dreaming stories that were his people’s spiritual source. When they were not exploring or hunting, Jimmy continued painting and Pat started to write. At home, far away from the hustle and bustle of the rag trade and the fickle art market, Jimmy continued to paint on his rough work table made from old planks, under a brush shade structure, driving 180 kilometres into Fitzroy Crossing every few weeks to drop off the work and pick up supplies. One of the many creative results of his time with Pat Lowe in the desert was Jilji 1990, a fascinating account of desert life and desert living, written by Lowe and illustrated by Pike. It was the first of several collaborations. During the eighties, when the Australian art world was beginning to open its eyes to the different styles and strands of contemporary Aboriginal art, Jimmy Pike’s work was exhibited alongside other Kimberley artists but just as readily fitted in shows featuring the younger urban artists emerging from city art schools that had been brought up in suburban surroundings. His powerful and distinctive use of colour and line reserved him an expressionistic corner in the middle of this growing diversity. Desert Designs was at the same time finding its place as a new icon of Australian fashion and contributing significantly to international perceptions of Australian culture. By the close of the eighties, he had become one of Australia’s most well known Aboriginal artists, receiving important commissions and travelling to the southern cities and overseas for openings and events. As he gained first a national and then an international reputation, he had successful exhibitions in China, the Philippines, South Africa, Italy and England, and produced work relating to his experiences in each of these countries. A gentle but determined man, Jimmy Pike was always patient with curious questioners when he made one of his infrequent visits to the city. Alongside his international fame in the world of art and design, his deep, velvety voice proclaimed his respected position as tribal elder, musician and singer of tribal songs. He was a man of extraordinary energy and mischievous humour. Time spent with him was often full of laughter, as he described the pleasures of eating roast feral cat for Christmas dinner, or explained how he made himself "invisible" when being chased by the police for yet another motoring offense. While he lived with Pat in his isolated desert homeland, they worked on a number of books together.

Amongst these were Yinti: desert child (1992), Desert Cowboy (2000) and Jimmy and Pat Meet the Queen (1997) - a delightful fantasy about Aboriginal land rights. In his own quiet way, Jimmy Pike, forced by circumstance into white society, turned his back on it, rekindling his sense of belonging to the land. Though he died of a heart attack on his outstation at sixty-two years of age, his work continues to celebrate that sense of belonging that asserts its core position at the centre of Indigenous identity.

-

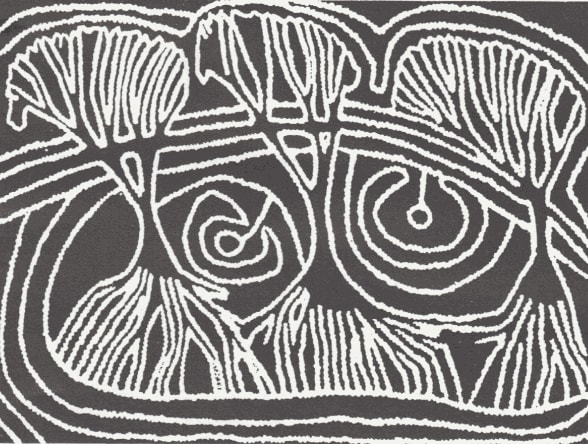

Larripuka Main Country, n.d.

Larripuka Main Country, n.d. -

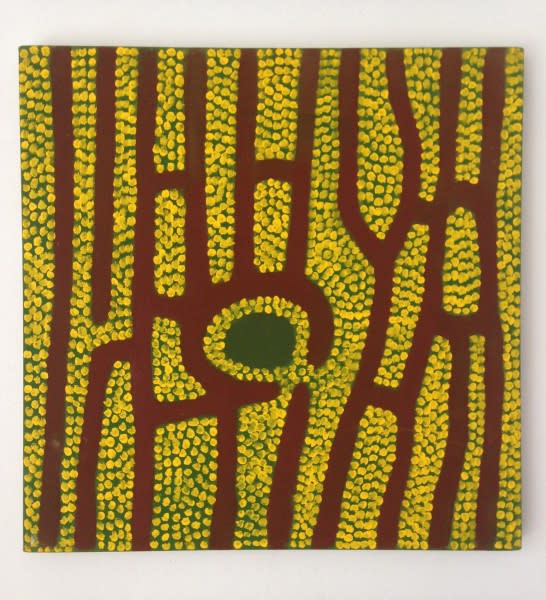

Kurriny Piyirnkujarra, n.d.

Kurriny Piyirnkujarra, n.d. -

Japingka Jila, 2002

Japingka Jila, 2002 -

Kalpurtu I, 2000

Kalpurtu I, 2000 -

Woman and Her Two Sons, 2002

Woman and Her Two Sons, 2002 -

Kalpurtu II, 2002

Kalpurtu II, 2002 -

Sandhill Country, 1988

Sandhill Country, 1988 -

Japingka Waterhole, n.d.

Japingka Waterhole, n.d. -

Japingka - Dreamtime Story II, c.1990

Japingka - Dreamtime Story II, c.1990 -

Katakarri, 2000

Katakarri, 2000 -

Untitled , n.d.

Untitled , n.d. -

Kalpurtu, c. 1990

Kalpurtu, c. 1990 -

Mantamarta, 2002

Mantamarta, 2002 -

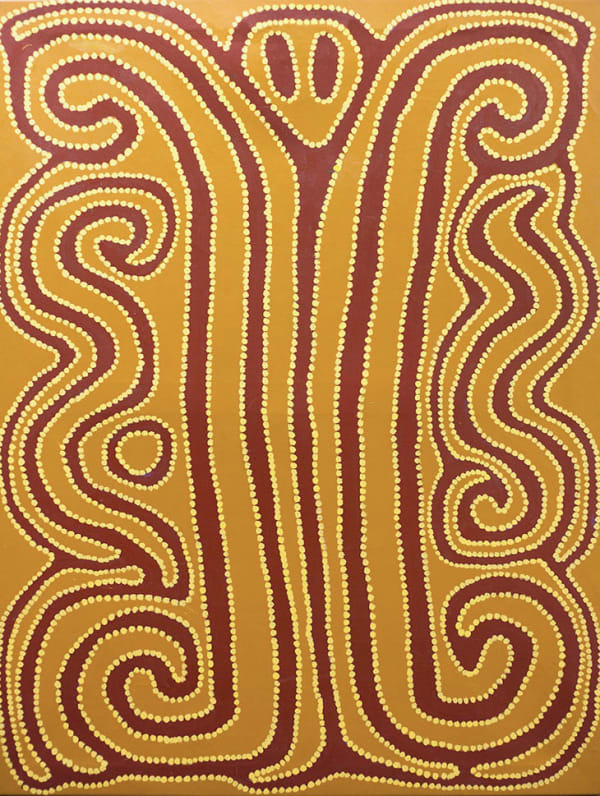

Kalpurtu, 2001

Kalpurtu, 2001 -

Kalpurtu, c. 2000

Kalpurtu, c. 2000 -

Bird, n.d.

Bird, n.d. -

Payarr Rockhole, n.d.

Payarr Rockhole, n.d. -

Jarlujangka Wangki, 1999

Jarlujangka Wangki, 1999 -

Japingka Map II, 2001

Japingka Map II, 2001 -

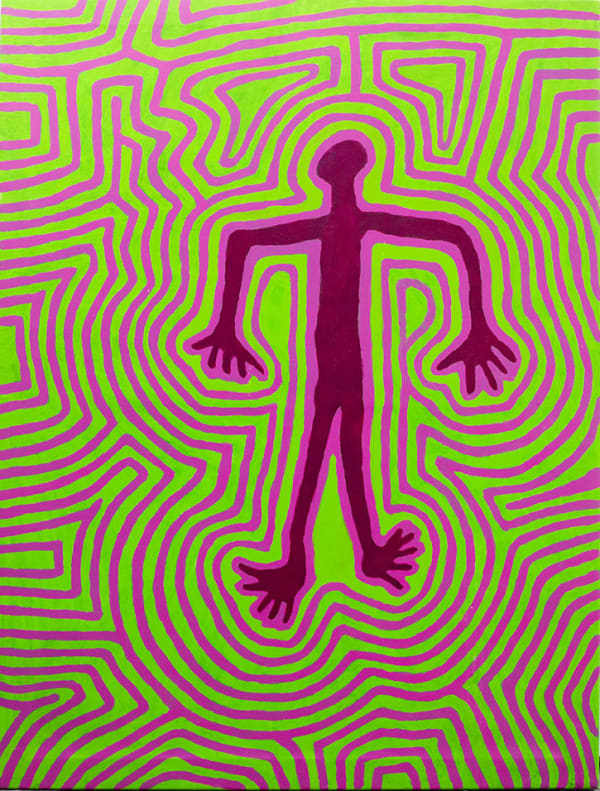

Body Painting, 2001

Body Painting, 2001 -

Japingka - My Country, c. 2000

Japingka - My Country, c. 2000 -

Jurtirangu - Para Karpan, n.d.

Jurtirangu - Para Karpan, n.d. -

Warnti, n.d.

Warnti, n.d. -

Ngurra Wanjulajarra, n.d.

Ngurra Wanjulajarra, n.d. -

Jila Japingka IV, c. 1995

Jila Japingka IV, c. 1995 -

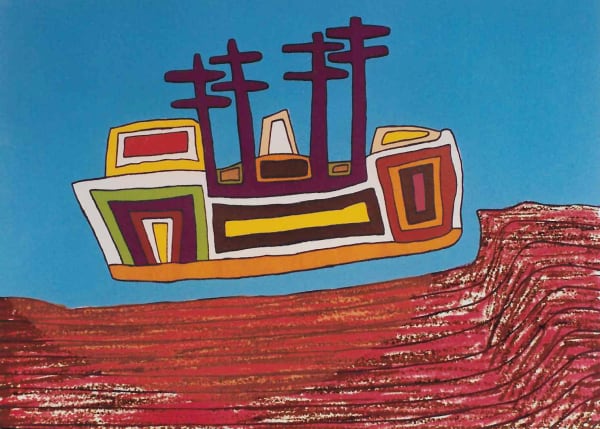

Kartiya Boat, c.1995

Kartiya Boat, c.1995 -

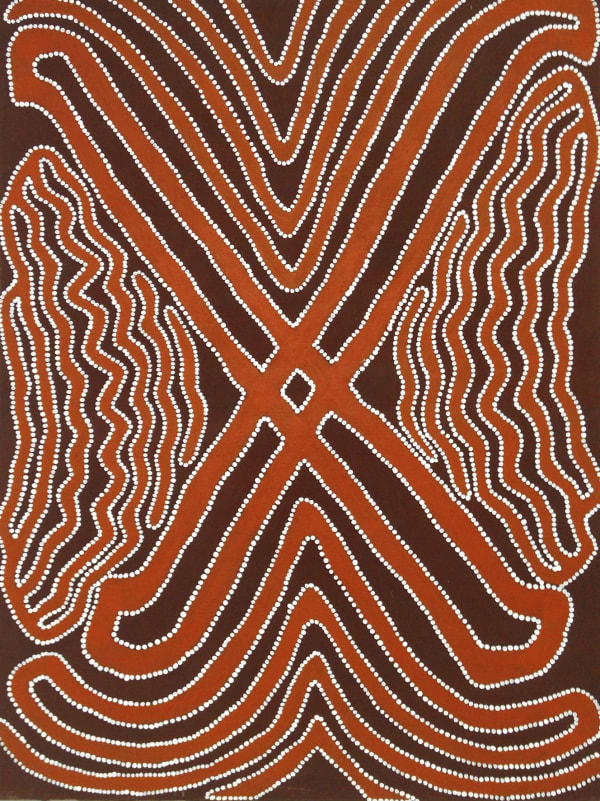

Partiri - Jilgikarraji, 1990

Partiri - Jilgikarraji, 1990 -

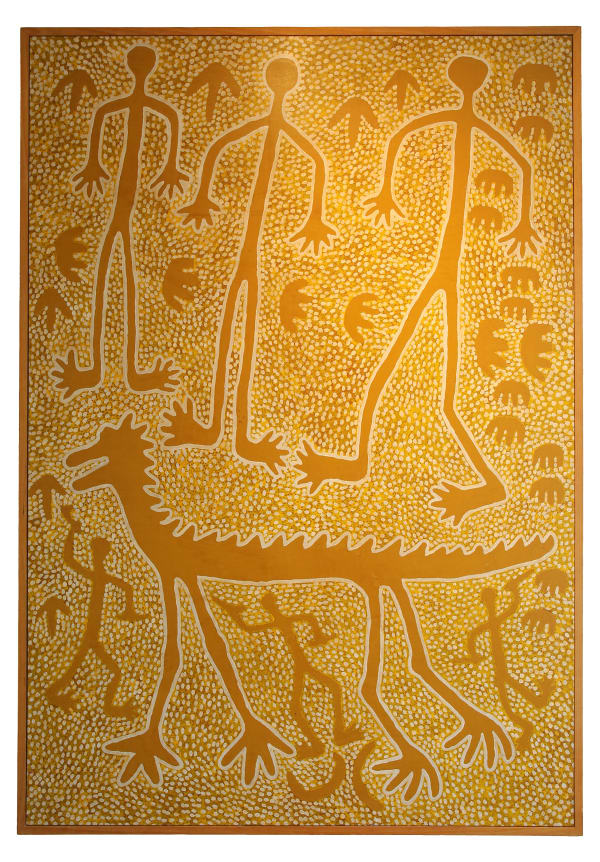

Parnaparnti and Kurntimaru II - Yellow Goanna and Black Goanna, 1990

Parnaparnti and Kurntimaru II - Yellow Goanna and Black Goanna, 1990 -

Untitled

Untitled -

Parnaparnti and Kurntimaru I - Yellow Goanna and Black Goanna, 1990

Parnaparnti and Kurntimaru I - Yellow Goanna and Black Goanna, 1990 -

Wuntarra Karraji, 1989

Wuntarra Karraji, 1989 -

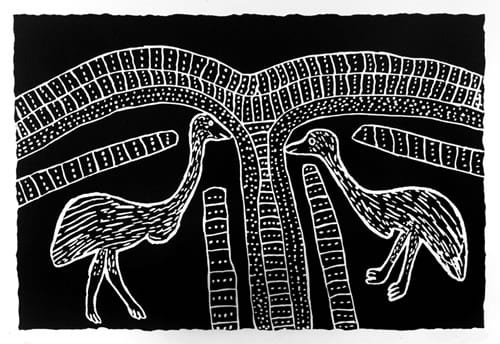

Two Karnanganyja — Two Emus

Two Karnanganyja — Two Emus -

Billabong, 1999

Billabong, 1999 -

Two Karnanganyja — Two Emus, 1989

Two Karnanganyja — Two Emus, 1989 -

Two Men Fighting, c. 2000

Two Men Fighting, c. 2000 -

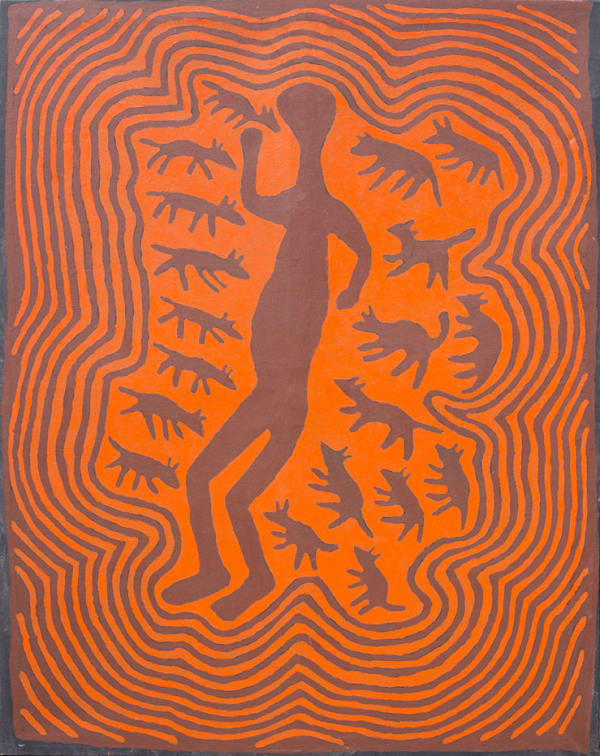

Kalpurtu, c. 2000

Kalpurtu, c. 2000 -

Body Painting, 2001

Body Painting, 2001 -

A Big Rockhole

A Big Rockhole -

Untitled

Untitled -

Larripuka II, 1996

Larripuka II, 1996 -

Kurntumaru and Parnaparti IV

Kurntumaru and Parnaparti IV

-

Private View Jimmy Pike

The Independent , 12 February 1991 -

Prints, Arts Review Featuring Jimmy Pike

Arts Review, 22 February 1991 -

Jimmy Pike At Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery

Harpers & Queen, 1 March 1991 -

Barbican, Aboriginal Art of Clifford Possum & Jimmy Pike

Time Out, 21 August 1991 -

Jimmy Pike Obituary

Rebecca Hossack, Independent, 8 November 2002 -

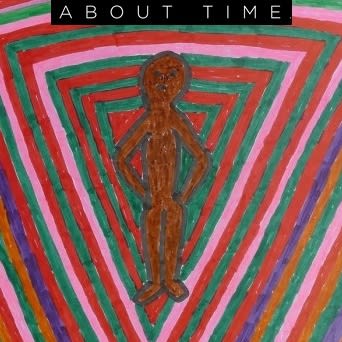

Jimmy Pike Exhibition

About Time Magazine, 1 July 2014 -

Jimmy Pike: A Desert Cowboy in London – Retrospective

Studio International, 8 July 2014 -

Jimmy Pike at Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery

Wall Street International, 21 July 2014

-

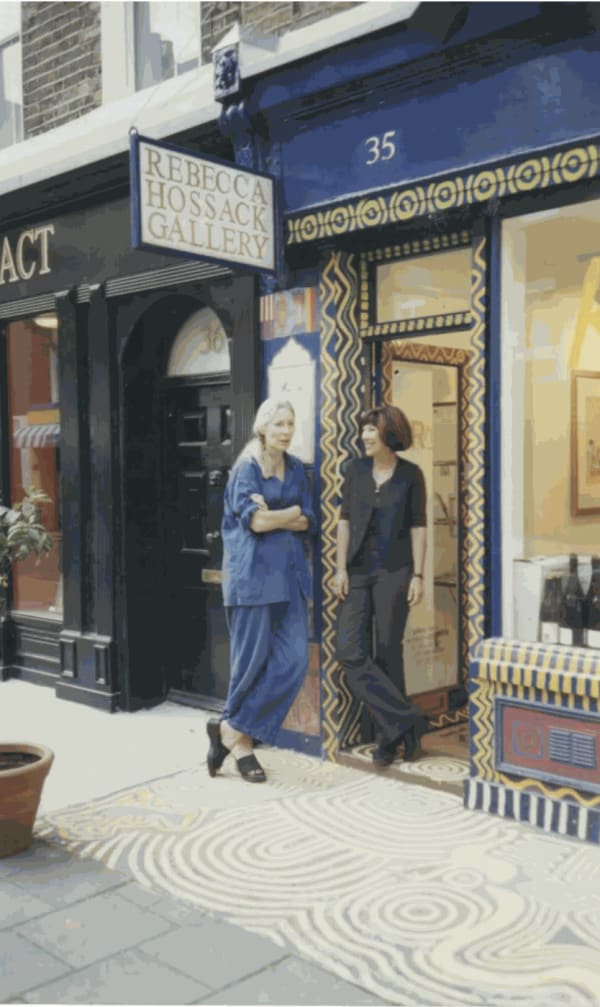

Rebecca Hossack outside the gallery with Jimmy Pike's banners

-

Jimmy Pike banners at the Rebecca Hossack Gallery for Desert Cowboy in London Exhibition

-

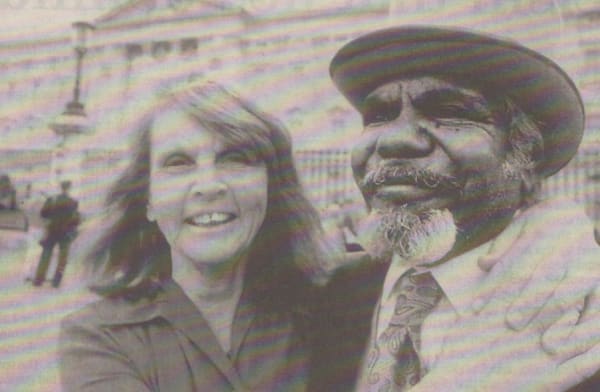

Jimmy Pike and Rebecca Hossack in Suffolk, 1 March 1991

Jimmy Pike and Rebecca Hossack in Suffolk, 1 March 1991 -

Jimmy Pike, Pat Lowe and Rebecca Hossack, 12 February 1991

Jimmy Pike, Pat Lowe and Rebecca Hossack, 12 February 1991

-

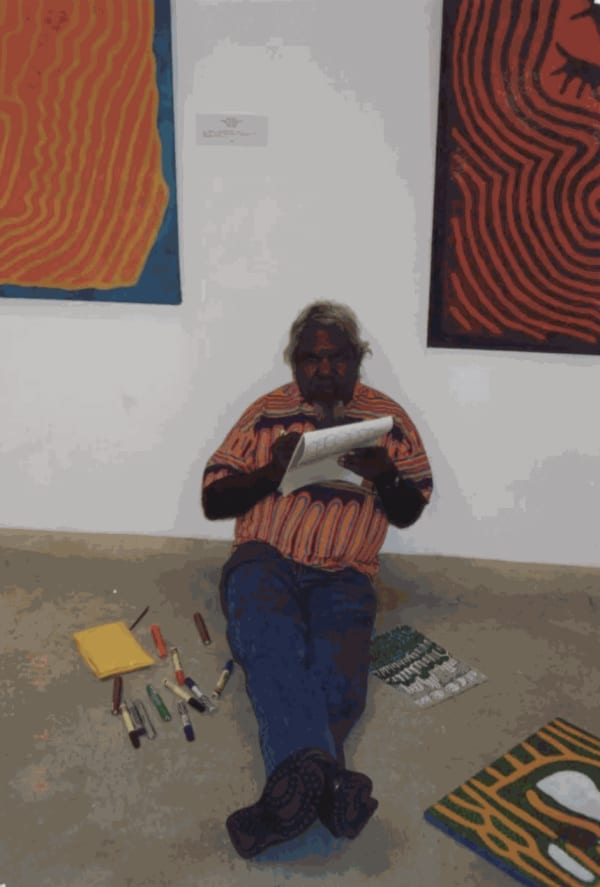

Jimmy Pike at his exhibition at the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery, 12 February 1991

Jimmy Pike at his exhibition at the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery, 12 February 1991 -

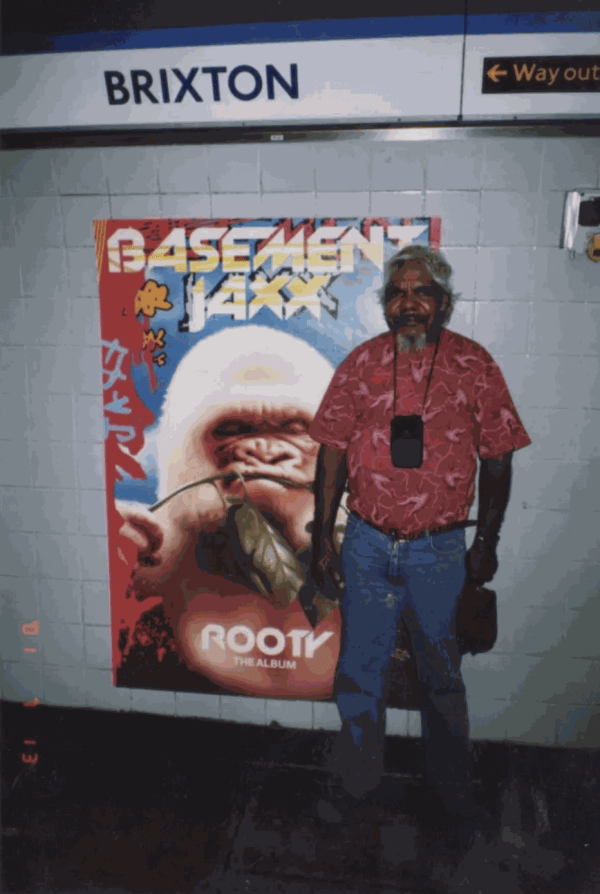

Jimmy Pike at the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery, 12 February 1991

Jimmy Pike at the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery, 12 February 1991 -

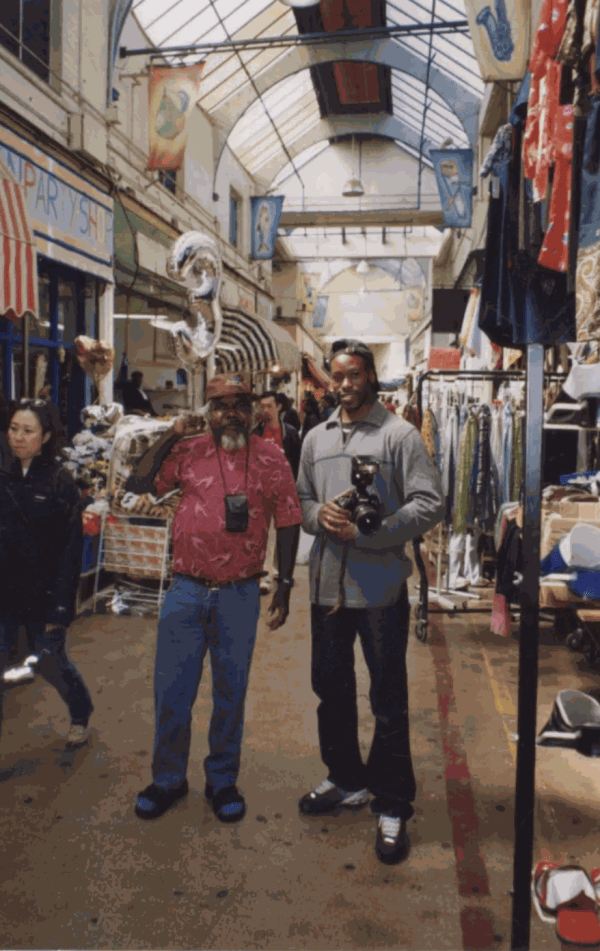

Jimmy Pike at Brixton Market, 12 February 1991

Jimmy Pike at Brixton Market, 12 February 1991 -

Jimmy Pike painting outside the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery, 12 February 1991

Jimmy Pike painting outside the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery, 12 February 1991