Kitty Kantilla

Overview

Kitty Kantilla was born at Piripumawu around 1928 and grew up at Yimpinari on the eastern side of Melville Island. After her traditional Indigenous childhood, Kantilla forsook the paperbark roof of her youth for mission life in her adulthood. The mission settlement located on the eastern coast of Bathurst Island some 100 kilometres across the waters to the north of Darwin had been established in 1911. Workers were rewarded for their agricultural labour with rations such as beef, flour, honey and tea to supplement their bush tucker.

In 1970 Kitty, along with a number of other countrywomen, created a tiny outstation in her mother’s country at Paru, on Melville Island just across the waters of the Aspley Strait within sight of the growing township of Nguiu. It was here that Kitty first began working as an artist, with a group of widowed women who became renowned during the early 1980s for their ironwood sculptures of ancestor figures drawn from the Purukupali legend.

Whilst in Paru, Kitty Kantilla produced carvings and tunga (bark baskets) that were marketed through Tiwi Pima (1978–89) when she was known as one of the Paru women. She began to paint on canvas and paper in 1992, supported by the infrastructure of Jilamara Arts & Craft Association, producing only occasional carvings from this time onwards. Kitty Kantilla later became known as the ‘first old lady of Jilamara’ and was a founding member of Jilamara Arts & Crafts.

Kitty Kantilla’s art, and indeed, all Tiwi art, is informed by the ornate body painting of the Pukumani (mourning) ceremony. What makes the art of Kitty Kantilla and those of her generation so important is the fact that the meaning of these designs has been largely lost since the missionary era. She was amongst the very last who inherited them intact.

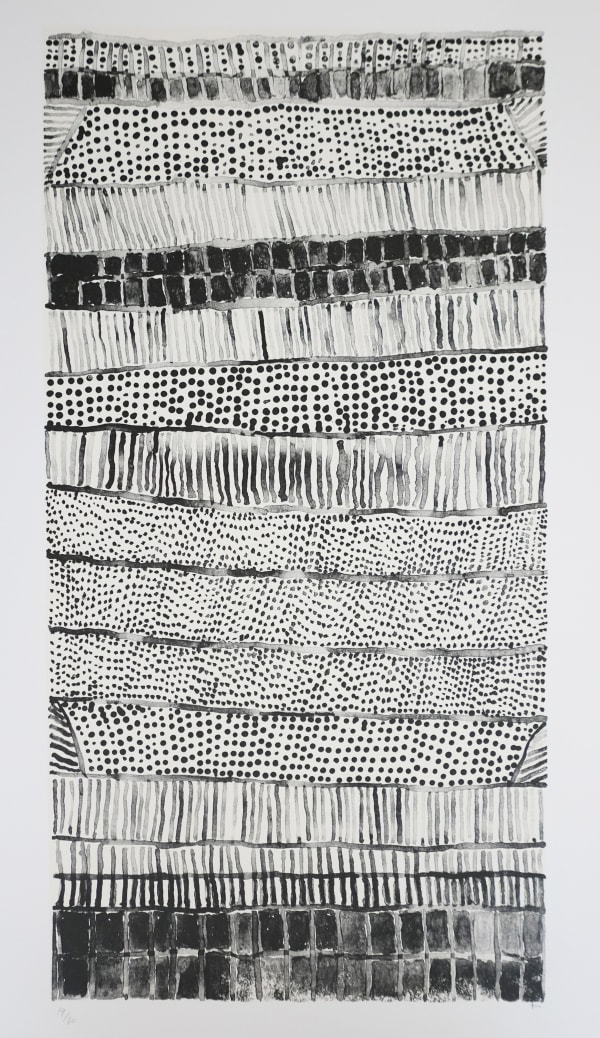

Her means were few: she needed only dots, lines and ochre colours to create infinite variations of rhythm, balance and beauty, of which no two are exactly alike. The powerful inwardness of Kantilla’s distinctive style hinges on its deep resonance with customary ritual. Kantilla’s sophisticated and seemingly abstract iconography eludes legible symbolism. For the viewer, Kantilla’s works are highly charged with ceremony, with something spiritual and untouchable.

Far from being non-representational, the different combinations of dots, lines and blocks of colour called jilamara (design), when combined, evoke elements of ritual and reveal the essence of Kantilla’s cultural identity. Like other Tiwi artists, Kantilla gained her artistic knowledge in ceremonial contexts before learning to express her individuality by carving and painting objects relating to the Pukumani ceremony.

Kitty once said of her art, “The jilamara that I do, it’s my father’s design. I watched him as young girl and I’ve still got design in my head. As a young girl, when my sister passed away, I watched him. When he died, I did the same design, right through Nguiu [Paru], I kept painting. When my husband died in Adelaide, they wanted to give me a widow’s pension but I said, ‘No, I’ll work, make jilamara, carving, make my own living’. Right through all the way, working everyday! When we gathered logs for carving, there was no transport! We carried them on our shoulder, walking, having a rest, walking a long way, heavy work. We worked at home [Paru], with no chainsaws, just tomahawk, carving, hard work. Then we would take the carvings by canoe, paddling across to Nguiu to sell them.”

Her artworks, regardless of medium, were always tied to the fundamental Tiwi creation story. Bima, the wife of Purukapali, makes love to her brother-in-law while her infant son Jinani, left lying under a tree in the sun, dies of exposure. Purukapali becomes enraged and, after his wife transformed into a night curlew, begins an elaborate mourning ceremony for his son. This was the first Pukumanu (mortuary) ceremony, telling how death first came to the Tiwi Islands. Considered the most important ceremony in a Tiwi person’s life, Pukumani is the final ritual which farewells the deceased through song and yoyi (dance) and safely sends their spirit to rest on Country.

Art critic Sebastian Smee most aptly described Kitty Kantilla as ‘a poet of small scale contrasts’ (2000: 22). In her final years, though frail, she could imbue her works, despite their lack of figuration, with her ambivalence towards tradition and evolution.

In 2000 Kitty participated in the Adelaide Biennale of Australian Art, and in 2002 she won the works on paper award at the 19th Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Awards in Darwin. Kitty Kantilla, was honoured with a posthumous retrospective exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria which opened in 2007 and toured nationally.

Works