Robert Campbell Jnr 1944-1993

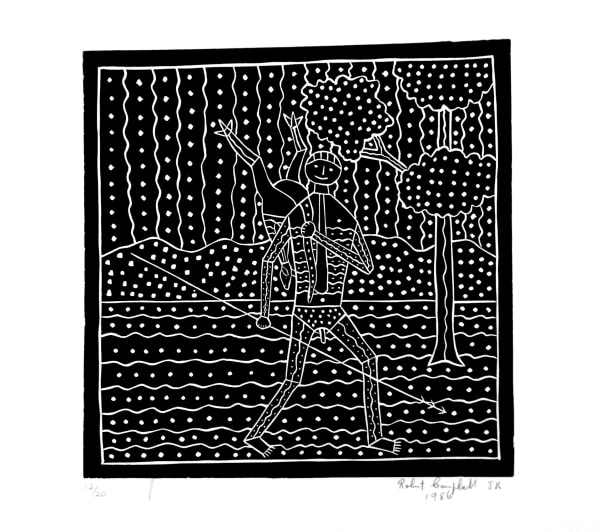

Very few visionaries in the history of contemporary art encompass joy and suffering so effortlessly as Robert Campbell Jnr (1944 - 1993). Born on 15 August 1944 at Kempsey, New South Wales, fourth surviving child of New South Wales-born parents Thomas William Campbell and his wife Lottie Ivy, née Sherry. Named after his uncle, Robert belonged to the Ngaku clan of the Dunghutti nation. Primarily a self-taught painter, Campbell began painting in the early 1980s. His striking, dynamic paintings are based on the patterning, colours and stylistic conventions of traditional Ngaku designs. They tell the story of his Ngaku people, entwined with the politics surrounding Aboriginal rights at that time.

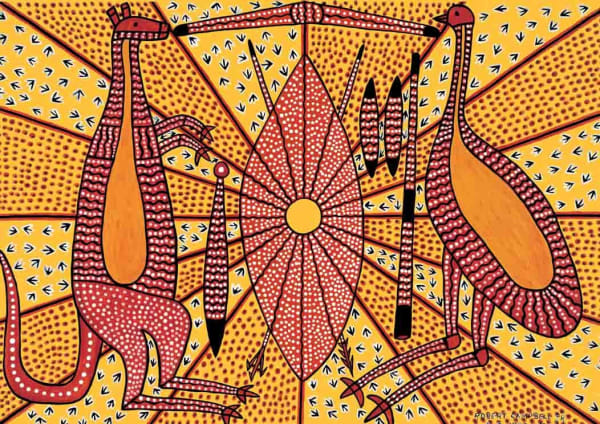

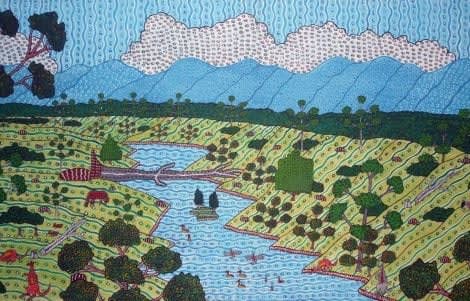

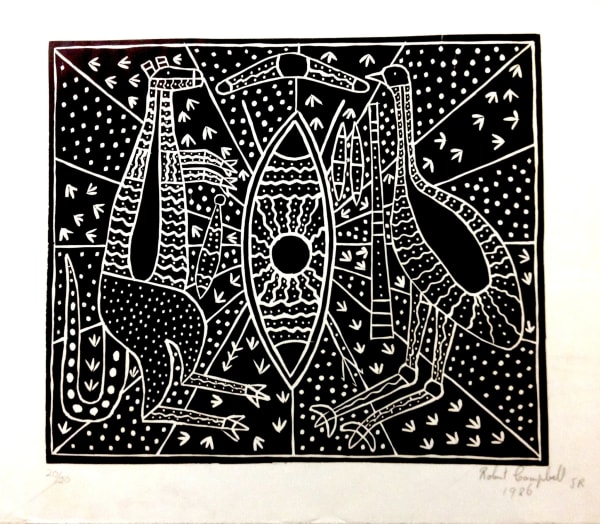

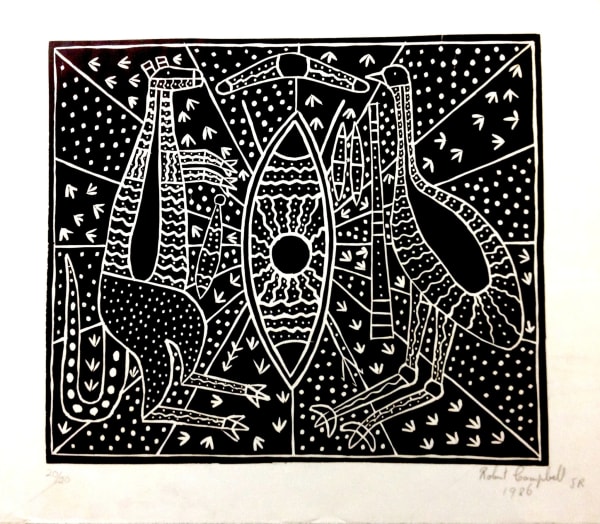

Robert Campbell Jnr’s father was a boomerang-maker, and would take off with his young son into the bush around the Macleay River searching for suitable cuts of wattle or mangrove for his work. Together they would then decorate the boomerangs with birds and animals. After leaving Burnt Bridge Mission school aged fourteen, Campbell continued to develop his artistic skills by painting local landscapes in gloss paint on cardboard, and selling them to passing tourists. After labouring at menial jobs away from home, Campbell returned to Kempsey and to painting.

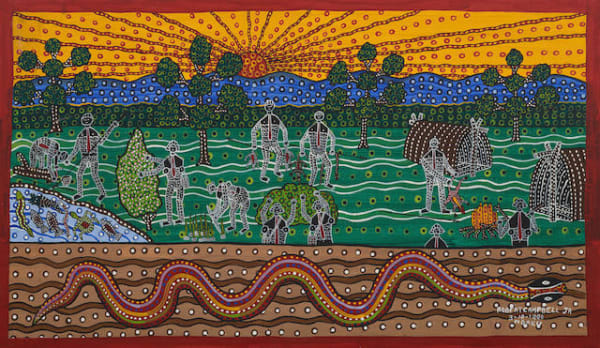

A visit to the Northern Territory in the late 1980s, during which time he encountered many indigenous artists and their communities, served as a cornerstone in the development of the artist’s bold, idiosyncratic style. From nostalgic childhood scenes of camp life and bush food gathering, to brutal scenes of white conquest, murder and the poisoning of waterholes, Campbell managed to convey a sense of unflinching observation of history - past and present.

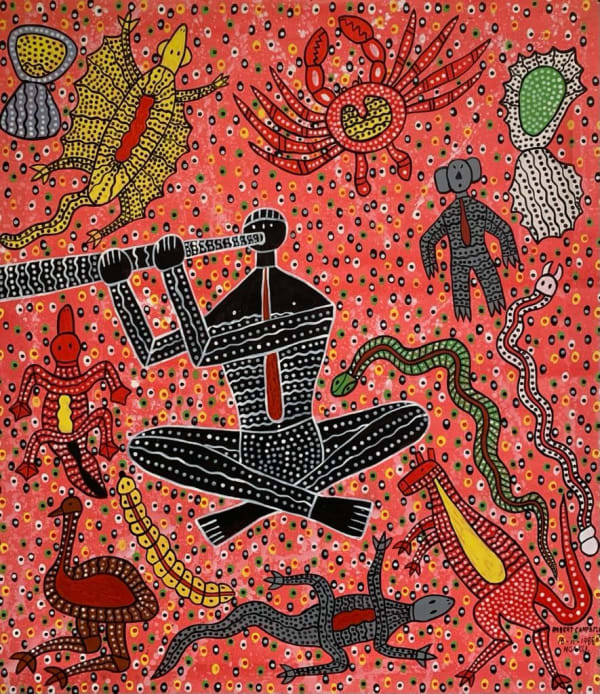

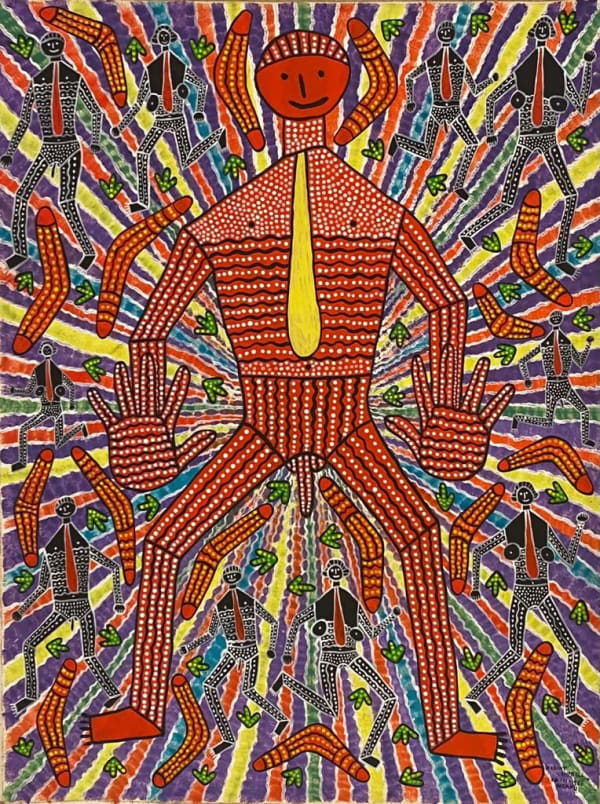

Taking up canvas and artist boards for the first time , he developed his idiosyncratic approach: a stylised, dynamic command of form, and a daring use of colour. Fusing sophisticated compositions with a raw, naive vision, Robert Campbell Jnr began to record the stories that he remembered from his childhood, as well as the brutal history of racism and colonialism, and the apartheid of twentieth-century Australia. Map of the massacres of blacks on the Macleay Valley, 1990, depicts the past rapes, murders and poisoning of water-holes. Campbell also painted Arcadian scenes of camp life, of food gathering and of Paradise lost, as in Sunset over the Macleay overlooking Euroka, 1990.

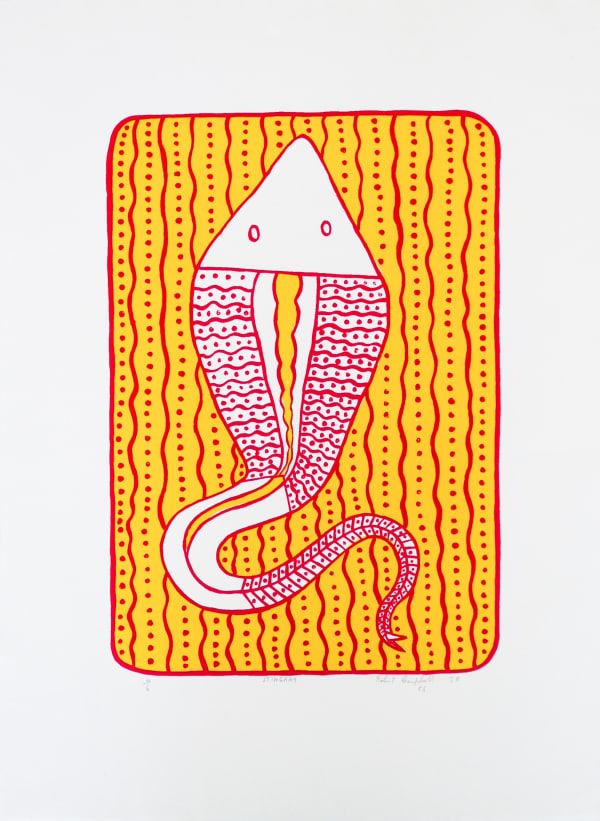

Throughout his distinctive oeuvre, the picture surface is animated by vivid decoration that recalls possum-skin cloaks and the fine engravings on Aboriginal shields, clubs and boomerangs of south-eastern Australia. The oesophagus-like red tie that appears on many of Campbell’s protagonists expresses ongoing relationships with the natural and supernatural worlds, and recalls the X-ray technique of Arnhem Land rock painting. Many works form sequential narratives, such as Campbell’s commemoration of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy set up in 1972 on the grounds of (then) Parliament House in Canberra.

Campbell’s pictures always exude confidence and frankness, and he managed to reconcile his personal experience with public expression, despite the former typically being a realm of inarticulate pain and the latter being in danger of sloganeering. Campbell’s bold imagery is a deliberate, incisive affront, but one that is also full of compassion and irrepressible humour. There is some-thing essential in his work: a feeling of jubilation in our humanity, which might seem strange arising out of such an oppressive social order.

Campbell died of heart failure on 14 July 1993 at Kempsey and, after a funeral at All Saints Catholic Church, was buried in the lawn cemetery, East Kempsey. His de facto wife Eileen Button, and their two sons and two daughters, survived him. He is remembered as ‘a quiet, gentle man’ with a keen wit. His self-portrait (1988) is held by the National Gallery of Australia, and his work is represented in national, State, and regional galleries, as well as private collections. Prior to his death (?), his work was the subject of numerous international exhibitions, including at the Rebecca Hossack gallery in London. He helped to assert the voice of Indigenous people living within the urban landscape, and continued to provide a unique indigenous perspective on the history of displacement and dispossession to this day.