David Surman

A journey through time – it crosses one’s mind while travelling

to Deptford on the South Bank of the Thames. Once a

significant dockyard founded in 1513 by Henry VIII whose

Royal Palace in Greenwich was nearby, today the district is

firmly on the cultural map. Rising from decades of doldrums,

it has triumphed as a nerve centre for emerging artists,

designers, musicians. Many of them can be found at work in

the Acme Factory, a former ship propeller foundry on

Childers Street.

'I enjoy working here', says David Surman cheerfully,

offering coffee and a croissant. His space on the ground floor

of the four-storey building bears all the hallmarks of the classic

artist’s studio, its surfaces strewn with canvasses, paints, other

essential tools. Dominating one wall is a large painting of a

female nude in motion, in bold yet nuanced colours. She

wields an axe which, despite its menacing overtones,

represents something distinctly more benign on closer

inspection.

'I was thinking of my mother and sister, cutting

rhododendrons', explains Surman. 'The image portrays the

mental energy one needs when moving from being passive to

productive activity. My aspiration is to communicate vitality,

and my inspiration was Gauguin'.

The French Post-Impressionist painter Paul Gauguin was

preoccupied with spiritual exploration, with a search for

something beyond the material world. This could also be said

about David Surman who channels spirituality through his

art. His expressive works address humanity’s disconnection

from nature, highlighting the environmental crises of our

industrialised world. 'Climate change, the impact of

technology on people’s lives – so many things are wrong.

Nature should be respected but we live in a world where it is

seen as disposable and inconvenient'. As such, Surman – who

works chiefly with oil and acrylics – currently favours animals

as his subject matter. They are, he says, both intrinsically of

nature and a symbol of humanity’s urge to cultivate and tame.

'These are often domesticated creatures because they are

human-like and a mirror for us. I work from my memories,

from personal experience. And I like to tell the story of what I

have seen and how I felt about it'.

Nature has always played an important role in David

Surman’s life. Born 1981 in Barnstaple, a small market town

in North Devon, in childhood he became fascinated by the

nearby village of Combe Martin, which is famous for two

things: the longest street in Britain (3.2 km) and its annual

celebration of the pre-Christian 'Earl of Rone' -Festival, the

latter featuring folk dancing and a host of pagan rituals. “This

had a big effect on me as a kid', he says. Year after year it put

me in touch with the ancient rawness of earth and fertility'.

The oldest of 5 children, Surman’s father served in the navy,

while his mother was a housewife who used her spare time to

draw and sculpt. And, naturally, her passion for creating

wielded a significant influence during his formative years. 'I

became lazy in things that didn’t interest me, he admits. When

one of his teachers said in weary resignation, 'You cannot just

do art, David', his response was simple and uncompromising.:

'I think I can'. Decades later, it’s a line that has served him

well.

Another seminal moment in Surman’s artistic development

came when he was 12 and the family exchanged the south of

England for the rugged wilds of the Western Highlands where

his father took up a job as a game keeper. Through long bus

rides to school, rivalry between English and Scottish kids and

lonely days, art remained a retreat. Having accumulated piles

of drawings, his father took him to Rob Fairley, a powerful

figure on the Scottish art scene and asked. 'What am I going

to do with my kid?' And so it happened that, at the age of 15

Surman began his artistic training in earnest before going on

to study Animation at Newport School of Art in the early

2000s, followed by an MA in Film Studies at Warwick

University in 2004. Today, like his artistic idols – Picasso,

Matisse, Modigliani who all drew, painted and sculpted– he

enjoys working across various media, embracing versatility.

The American painter Jackson Pollock once said, 'Artists are

more spiritual than the best priest or rabbi'. Surman nods in

agreement. 'Hundred percent true', he says. Through the

creative process we can explore our innermost thoughts.'.

God, he believes, welcomes our doubts. 'Questions are

motivators and open doors'. He thinks for a moment and

then draws a comparison between optimism and hope. 'An

optimistic person tends to be oblivious to harsh realities. Hope

represents positivity, responsibility. The route to beauty is

hope'.

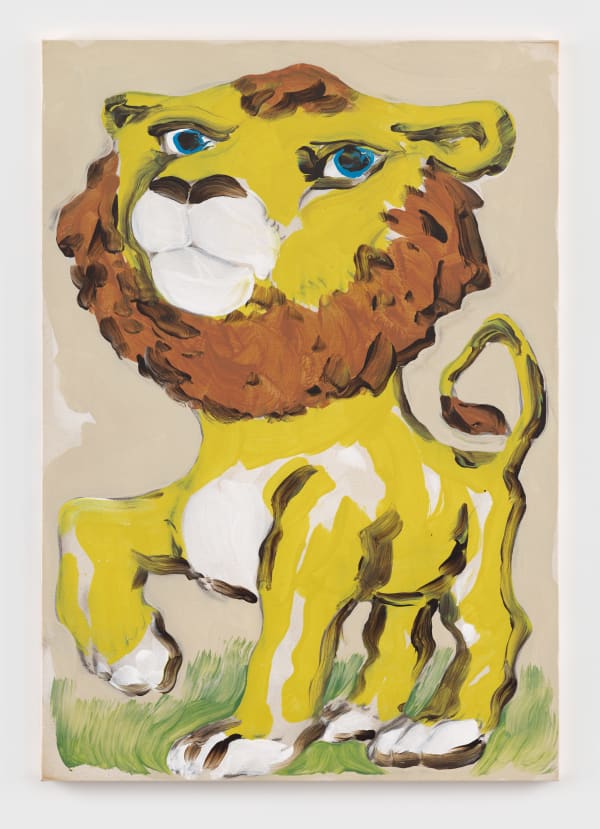

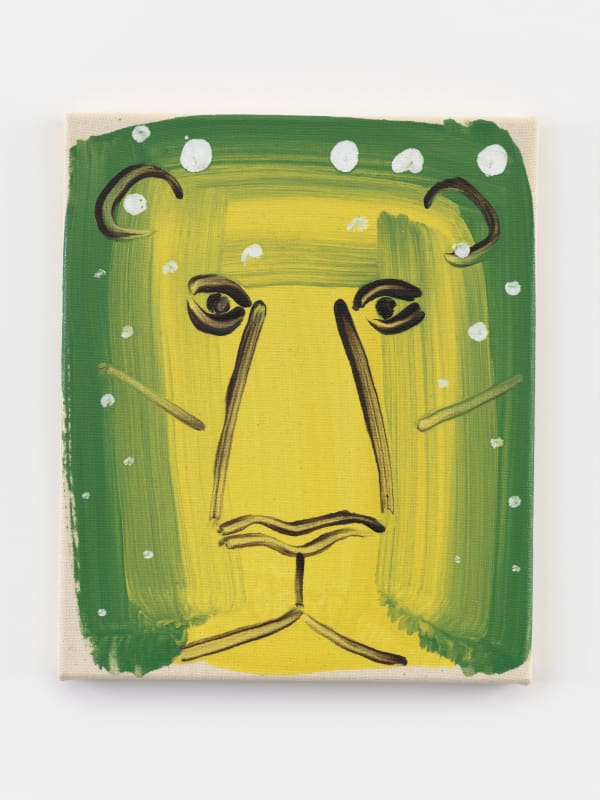

One last question before David Surman makes his way to his

partner, the multi-media artist Ian Gouldstone with whom he

lives nearby: why did he choose to paint a lion, which falls

outside his usual remit of representing the domesticated

animal? 'The inspiration was the Golden Age of Hollywood',

Surman answers. 'Quentin Tarantino and David Lynch both

said in separate interviews that cinema had ended in 2019

with a shift to TV. So, I wanted to paint an image of the last

MGM king of beasts. Actually, they used six roaring lions as

their iconic logo'.

Lynch and Tarantino were right: cinema has been sinking into

a slow demise over the past decade. If artists like Surman

continue to work and ask spiritual questions via the canvas, art

will, for now, remain safe from such a fate.

-

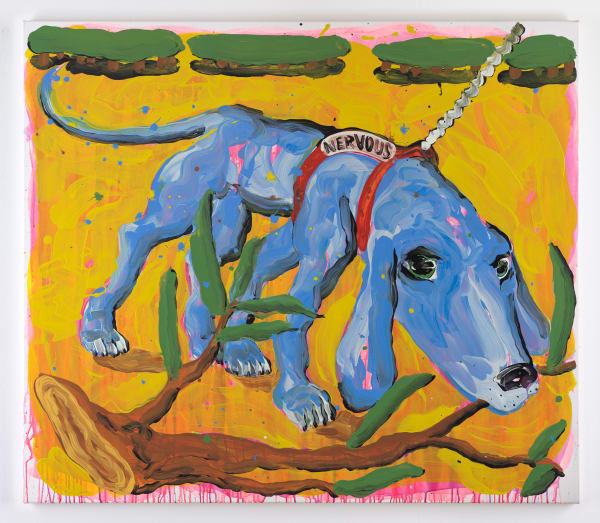

Ambitious Dog, 2024

Ambitious Dog, 2024 -

GOD DAM (After Rufino Tamayo), 2023

GOD DAM (After Rufino Tamayo), 2023 -

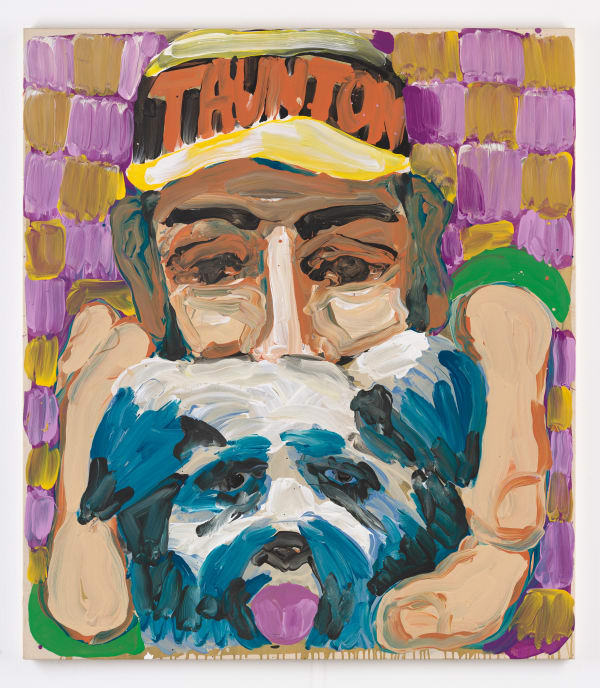

Taunton Dog Sniffer, 2024

Taunton Dog Sniffer, 2024 -

Selkie, 2024

Selkie, 2024 -

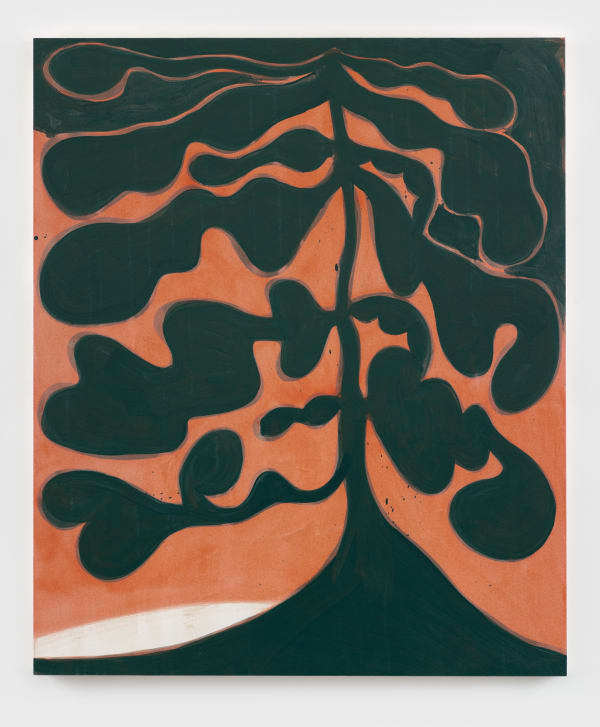

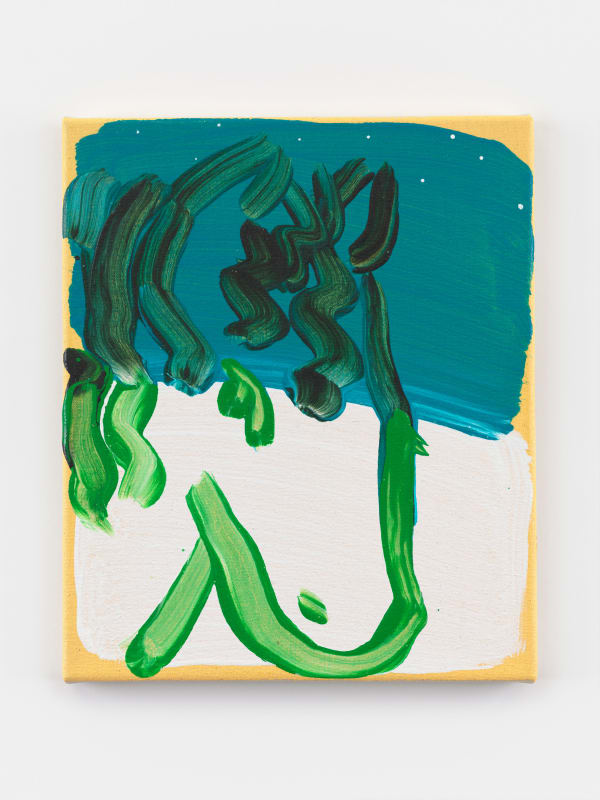

Tree, 2023

Tree, 2023 -

Kaboul, 2023

Kaboul, 2023 -

Where Am I Going?, 2023

Where Am I Going?, 2023 -

An English Pony Walking from Paris To Berlin , 2023

An English Pony Walking from Paris To Berlin , 2023 -

Lion in the Bush, 2023

Lion in the Bush, 2023 -

Sacred Girl , 2024

Sacred Girl , 2024 -

Sunbeam, 2024

Sunbeam, 2024 -

Boyhood Memory , 2024

Boyhood Memory , 2024 -

Die Winterreise , 2024

Die Winterreise , 2024 -

Sleeping Queen , 2024

Sleeping Queen , 2024 -

The Longest Night, 2023

The Longest Night, 2023 -

Pit Pony , 2023

Pit Pony , 2023 -

Ruby Heart , 2024

Ruby Heart , 2024 -

Yearling , 2024

Yearling , 2024 -

Eucalyptus, 2025

Eucalyptus, 2025 -

Kelpie Of Loch Ailort, 2024

Kelpie Of Loch Ailort, 2024 -

Old Stew Head, 2025

Old Stew Head, 2025 -

Clarion Call, 2024

Clarion Call, 2024 -

Leo The Lion (Art For Art's Sake), 2025

Leo The Lion (Art For Art's Sake), 2025 -

Icarus And Daedalus, 2024

Icarus And Daedalus, 2024 -

The Explorers, 2025

The Explorers, 2025 -

Bathers At K'gari, 2024

Bathers At K'gari, 2024 -

Midday Sun, 2023

Midday Sun, 2023 -

Ostracon, 2025

Ostracon, 2025 -

The Living Mountain, 2024

The Living Mountain, 2024 -

A Frog In An Endless Pond, 2024

A Frog In An Endless Pond, 2024