Trevor Nickolls

Trevor Nickolls (1949 – 2012) was born and raised in the suburbs of Adelaide, the capital of South Australia, and began drawing and painting in early childhood, at the age of eight. During the late 1970s, the intellectual climate, strongly influenced by post-modernism, saw the concept of ‘Aboriginality’ take hold for the first time in white Australia. Nickolls began to interrogate his own Aboriginal heritage during this time.

Self-consciously operating within the paradigm of Western art, Nickolls drew upon both ancient and modern iconography as he strove to articulate the uneasy fault-line that underpinned both an identity and a society built upon the disavowal of its sacred past. During his post-graduate studies at the Victoria College of Art in 1979, Nicholls met the Papunya artist Dinny Nolan Tjampitjinpa, who was exhibiting in Melbourne. Dinny Nolan generously shared his tribal wisdom and artistic knowledge with Nicholls, who later described the encounter as a turning point in his life and work.

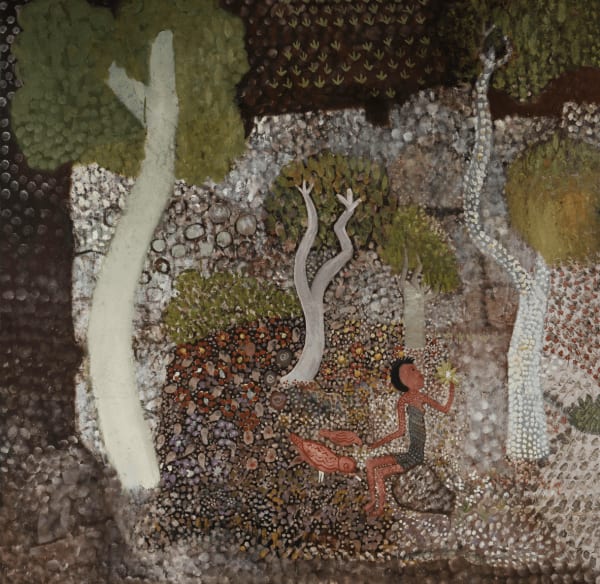

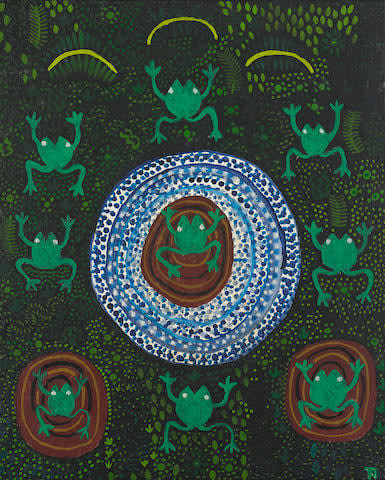

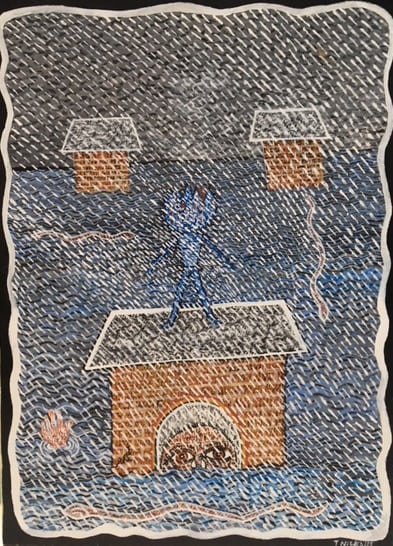

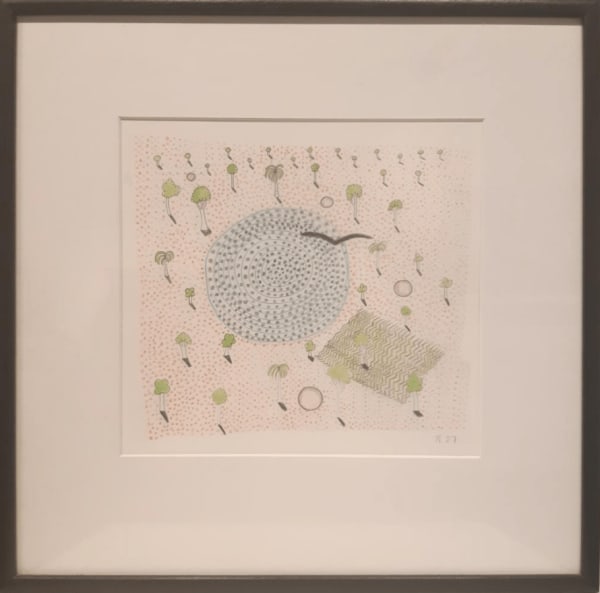

By the late 1970s, the Papunya artists had gained international acclaim for their unprecedented transposition of their millennia-old visual traditions into a fine art context- without compromising its strong spiritual conceits. The interaction with Nolan inspired Nicholls to synthesise elements of Western and Indigenous iconographies in his own artistic practise. The dot-and-circle technique of Desert painting and the deliberate addition of rarrk cross hatching enriched Nickolls’ love of dense and complex textures. He found that ancient techniques had a surprising resonance with the scientific view of modern life, commenting ‘everything is moving… you can look at things in a molecular way’. His appointment as an education officer at his alma mater the following year allowed Nicholls to travel to the outback, meeting Aboriginal artists and elders throughout Arnhem Land and seeing traditional rock paintings in situ. His understanding of the Aboriginal relationship to the land was no longer only an intellectual one; ‘I was right in it’, he says, ‘it wraps itself around you, full of spirit, the space, the Dreaming, imagining how it was once’. A new mood of relaxation and fulfilment permeated Nickoll’s work of this period in the late 1970s. Cramped urban complexities gave way to an elemental landscape where figures, trees, animals and waterholes were held in a direct frontal foreground, confronting and engaging the viewer with a powerful sense of mythical presence. Yet, his despairing disillusionment towards the poverty-stricken conditions of some industrialised Aboriginal settlements introduced a new level of uncomfortable duality in the artist’s practise. Working in Melbourne and Sydney during the 1980s, Nicholls coined the term ‘Dreamtime – Machinetime’ to describe the divide between Aboriginal and Western cultures. ‘Dreamtime’ reflects an innate and harmonious affinity with land as upheld by Aboriginal tradition, whilst ‘Machinetime’ refers to the alienated estrangement from the earth induced by hostile urban living. Often tightly juxtaposed within a single picture plane, these two realities collide abruptly with contrasting areas of colour, texture and spatial composition. A Rainbow Serpent contorts into symbols of currency, and urban towers become threatening monsters avariciously swallowing lone city-dwellers.

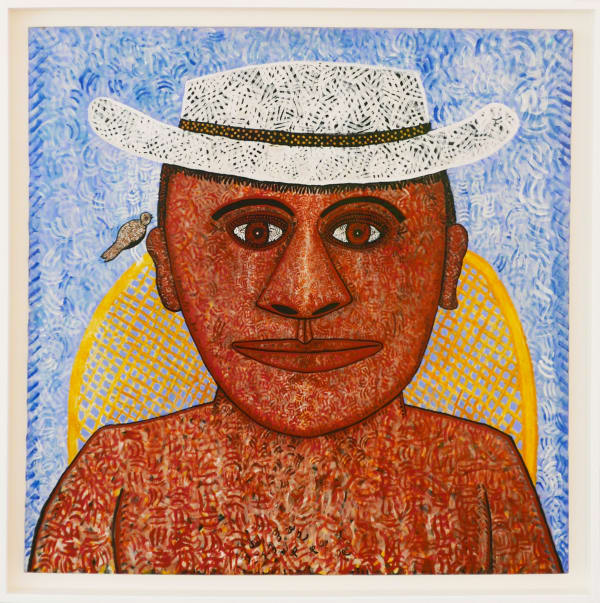

Nickolls gained international acclaim when he was selected alongside Rover Thomas to show a suite of 30 paintings to represent Australia at the 1990 Venice Biennale. His ability to inscribe his paintings with an experiential narrative sense – at once humorous and biting – implied an autobiographical leaning, attracting attention for their bold and provocative honesty. His recurring self-portraits chart the development of his idiosyncratic style, reflecting the universal dilemmas of contemporary life as much as his own fears and longings. From the early to mid 2000’s, the artist entered a phase of restrained painterly technique, with fundamental formal symbols such as a boomerang or spear thrower inhabiting a sparse, semi-abstract field. These quieter, somewhat meditational works, predominated by warm earth tones and traditional patterns, are imbued with a more solitary sense. By contrast, the artist’s late style of his final years saw the re-emergence of his iconic complex surface and exuberant colourism: a testimony to an ongoing sensitivity to his breathing environment that never lies entirely at rest. Since first exhibiting his Dreamtime-Machinetime images in Canberra in 1978 Nicholls participated in of more than 50 group and solo shows across Australia, in addition to several in Europe and the United States. C He was a finalist in the Clemenger Contemporary Art Award at the National Gallery of Victoria in 2009, a major survey exhibition of his work toured Australia in 2009–10, and in 2013 he posthumously won the Blake Prize for religious art.

His work is held in numerous prestigious collections of art, including the National Gallery of Australia, Victoria, and the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Adelaide. - 2012